Much of our understanding of this country’s racial past is rooted in the American South. Slavery, emancipation, the modern struggle for civil rights – for many, all of this happened, in effect, very far away. It was someone else’s problem. But this history isn’t relegated to a few select states, it’s all around us, and the first leg of our DMV Bridge Journeys focused on revealing the complicated past that’s right outside our doors.

Bethel AME Church, Easton, MD

Black history and community can often be found in churches. Maryland’s Eastern Shore is no exception. Our journey began in Easton, MD’s Hill District, one of the oldest free Black communities in the United States. Founded in 1788, it’s home to the Bethel AME Church – the region’s first (but far from last) offshoot of the African Methodist Church – whose current structure was dedicated by Frederick Douglass in 1878. Our final destination, however, was a bit unexpected: a Quaker meeting house.

Third Haven Meeting House, Easton, MD

The Third Haven Meeting House is generally considered to be the oldest surviving Quaker meeting house. Unlike the AME churches that proliferated after Reverend Shadrack Bassett came to Easton in 1818, this meeting house, like the Quaker religion itself, was predominantly white. But it serves to reveal the complicated nature of the region’s racial past. The Quakers were on a whole abolitionists, and the democratic nature of their meetings allowed anti-slavery sentiment to be brought to the forefront. Direct opposition to slavery itself was difficult, as the institution was so firmly rooted in the communities around them, but their beliefs and activities are an important reflection of a sometimes unfortunate truth: change requires agitation, and more often than not that agitation must come from a position of power. And in the 18th and 19th centuries, if you were powerful, you were undoubtedly white.

But that wasn’t always the case.

Frederick Douglass is perhaps one of the Eastern Shore’s most famous residents. Born into slavery, Douglass learned to read and, upon escaping captivity, became through his writings and preaching a leader in the Abolitionist Movement, a counter-argument to the perception that slaves lacked intellect. He was widely-known, widely-read, and widely-respected – mostly in the North, to be fair – a man who had escaped his shackles to establish his own position of power. Today he is considered one of the most important men in American history, venerated by many as a hero of Abolition. But even in the 21st century, he’s still not venerated by all.

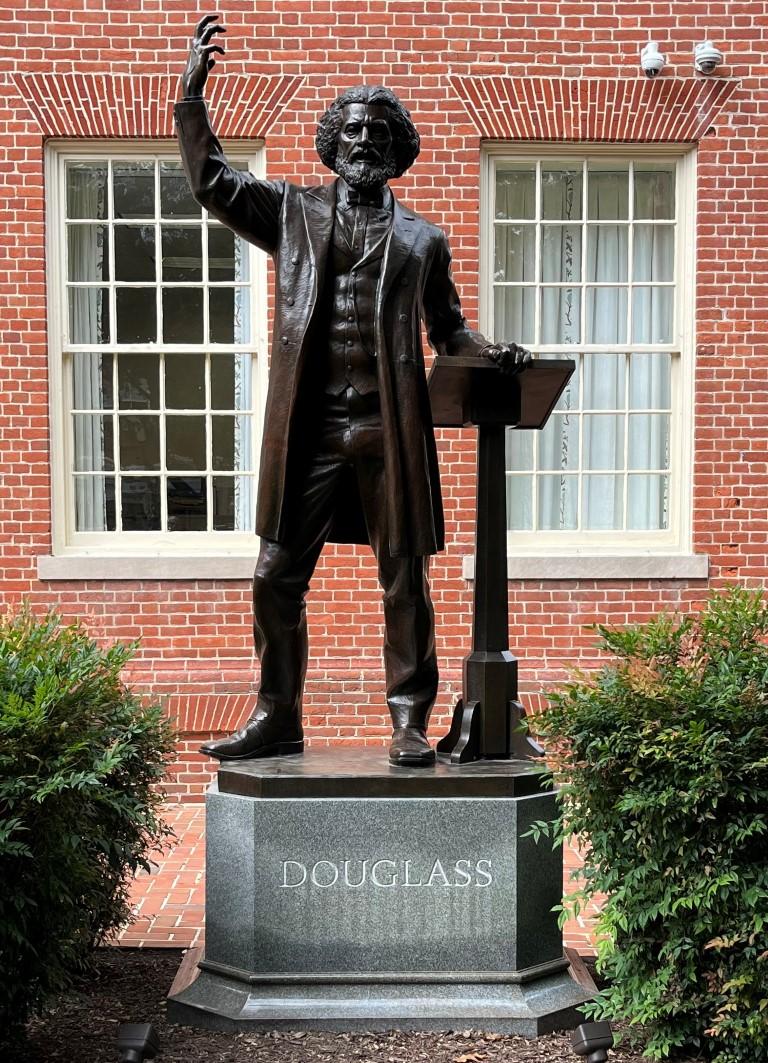

Our group learns the history of the Frederick Douglass statue at the Talbot Co Courthouse, Easton, MD

Our group was met at the Talbot County Courthouse in Easton by Harriette Lowery, a historian with strong ties to the region. The courthouse, where Douglass delivered his “Self-Made Men” speech and a stone’s throw from the jail where he was once imprisoned after an escape attempt, is prominent home to a statue of the abolitionist, erected in 2011. A monument to a great American, the region’s most famous native son, seems like a no-brainer. But Douglass was also a Black American, and the installation of the statue was met with protest. During its early days the statue was guarded from vandalism by local residents 24 hours a day, and even to this day the area is monitored by security cameras.

The Frederick Douglass statue at the Talbot Co Courthouse, Easton, MD

The dichotomy of racial thought that still pervades the area is best reflected in another statue that for a decade shared the courthouse lawn with Douglass. “The Talbot Boys” was erected in 1916 to honor the county’s Confederate dead, a county where Douglass was once enslaved, and after an initially failed 2015 movement it was finally removed in 2021.

St. Stephen's AME, Unionville, MD

Both Harriette Lowery and our guide for this leg of the journey, Dr. Bernard Demzcuk, are members of the congregation St. Stephen’s AME. A ten-minute bus ride from the Talbot County Courthouse, it’s a relatively unassuming building that belies a more storied past.

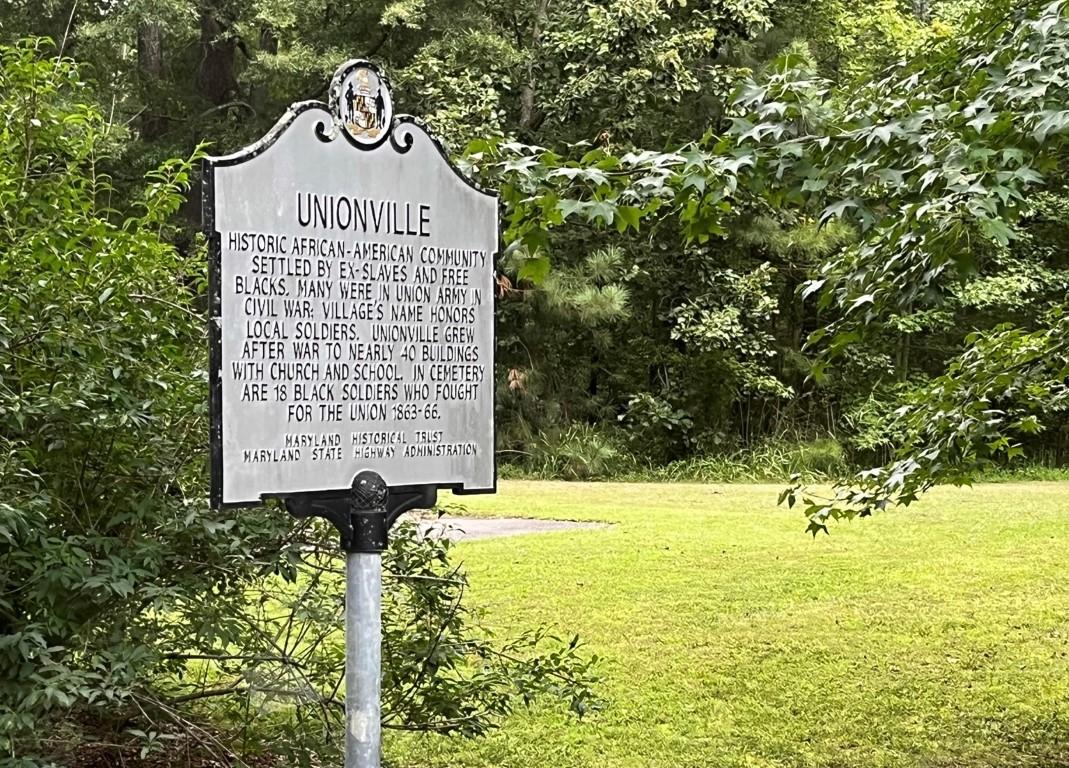

A historical marker details the origins of Unionville

In 1867, 18 Black soldiers, returning from fighting for the Union in the Civil War, were each granted tracts of land by the Quaker owners of the nearby Lombardy Plantation on the promise that they would build a church and a schoolhouse. This community would come to be known as Unionville, and the promised church, St. Stephen’s AME. The church’s main building is now the oldest remaining structure in Unionville, and still hosts an active congregation led by Reverend Nancy Dennis. In the cemetery out back, abutting the marshy lands once worked by themselves and their ancestors and facing east towards Africa, are the graves of those 18 soldiers who first settled in Unionville. Like St. Stephen’s, they’re a reminder of the resiliency of the free black communities, a storied presence in the area’s history but one that is too rarely celebrated.

The graves of the 18 Black soldiers who established Unionville

En route to our next destination, Cambridge, the group is reminded that Frederick Douglass isn’t the area’s only celebrated formally enslaved person who led an abolitionist charge. Along Route 50 stands a mural by Michael Rosato that celebrates figures from the region’s racial past, among them Gloria Richardson, a leading local figure in the fight for civil rights, and Harriet Tubman. Tubman is glimpsed once more in a newly-erected statue outside of the Cambridge Court House, a fitting reminder of her historical – and local – importance on our way to Race Street in downtown Cambridge.

Race Street, Cambridge, MD

Race Street, a name unrelated to its racial history, was once the dividing line between the white and Black communities in Cambridge. It’s now home now to a block-long Black Lives Matter mural painted by volunteers from the community. And only a couple hundred feet away, tucked in away in a tree-lined alley, is another mural, this one also painted by Michael Rosato and also featuring Tubman. But here she dominates, a trompe l'oeil depiction that breaks through the wall with an outstretched hand of welcome and assistance to those in need. A monumental tribute to a monumental figure in American history.

Race Street Harriet Tubman Mural by Michael Rosato

Behind the mural wall lies the Harriet Tubman Museum & Culture Center, and a bit further, Art Bar 2.0, an event venue and performance space lined with contemporary works by Black artists. Owned and operated by the Alpha Genesis Community Development Organization, whose leaders Adrian Holmes and Jermaine Anderson spoke with our group about local history and the hurdles faced in operating a Black-owned business, the space is a celebratory landmark of the local Black community. From Race Street to the Tubman Mural to the vibrant interior of Art Bar 2.0, it’s impossible not to get a tangential sense of the struggles and the joys of Cambridge’s racial past, present, and future.

Like many cities with Black citizens suffering under the injustice of white supremacy, Cambridge in the 1960s was home to a robust – and unfairly targeted – Civil Rights Movement, this one led by local activist Gloria Richardson. And like many of those other cities, a race riot occurred here, centered on the Black commercial center Pine Street. Incited by the murder of activist H. Rap Brown by a sheriff’s deputy during a protest march to Race Street, the ensuing unrest saw the burning of two blocks of Black-owned homes, businesses, and a school. On a bus ride down the street to our next destination the scars were not immediately evident, but the memories still remain.

Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Visitor Center, Church Creek, MD

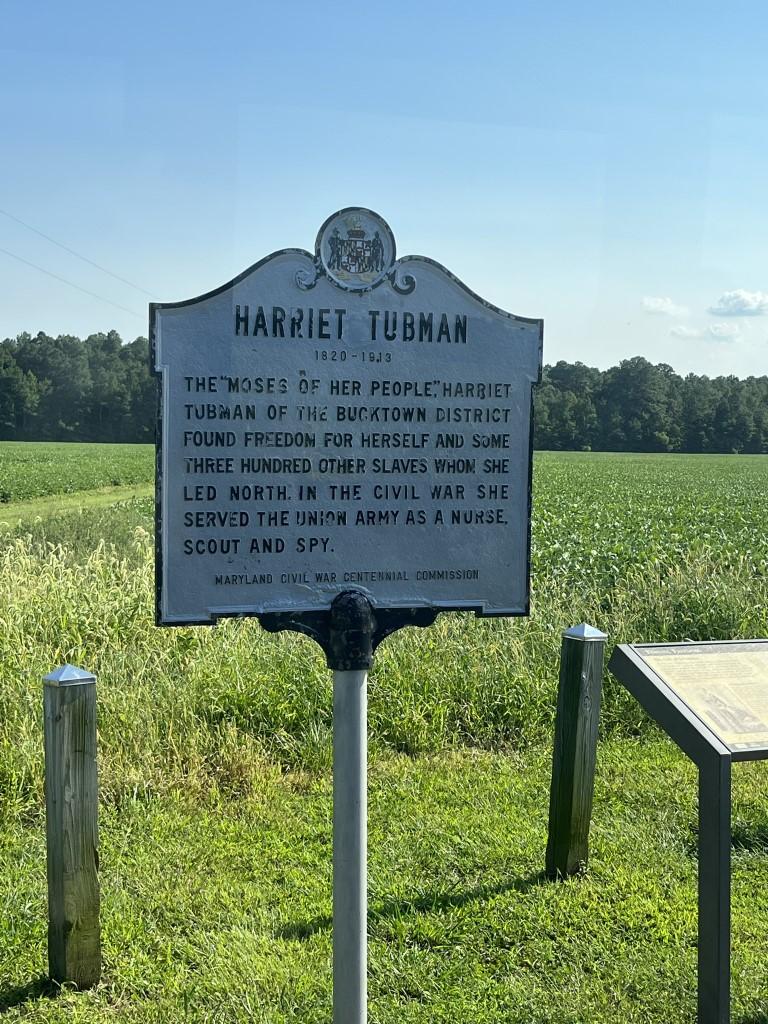

Our last stop on the journey was the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Visitor Center. Housed in four barn-like structures and situated in the swampy reeds of the Blackwater National Wildlife Reserve, an apt evocation of the barns where escaped slaves took shelter and the marshes through which Tubman once led them, it’s an educational center for the slave turned abolitionist (and later suffragette) and the Underground Railroad network that she utilized to free approximately 70 enslaved people. It’s also only a short ride through the low-lying farmland to the plantation lands where she spent her youth in captivity, and the general store where she suffered the traumatic head injury – a counterweight thrown by an overseer at another enslaved person attempting to flee, one that hit Tubman instead – that would set the course for her future. Plagued by headaches, seizures, and vivid dreams, she came to perceive these as divine visions, a perspective that would inform her actions as freer of slaves and fervent abolitionist.

Historical marker near where Harriet Tubman was enslaved in her youth

Living in this region, it’s not hard to see the history that surrounds us. History of battles and bills and presidents that stretches back hundreds of years, taught in history books and subject to endless hours of educational programming. But the most important history is that which for many remains hidden. It’s the story of enslaved peoples and free Black communities, churches and streets and monuments to figures that fought against injustice. And it’s that injustice itself, injustice that is both a remnant of the past and yet still alive in the 21st century. Histories left unrevealed are histories that are unable to inform and teach. From the widespread unrest in the summer of 2020 to the fervent reaction against Talbot County’s statue of Frederick Douglass, it’s clear that the fight for racial justice is ongoing within our region, and the more that’s revealed to us the stronger we can be as leaders of a positive charge to radical change.

Thank you to our generous partners for supporting - and joining! - the DMV Bridge Journeys